Now in Yangshuo, our first days in China have been devoted to building a foundation for communication during our travels here.

We now have four days of “survival Chinese” under our belt. Since we started from zero, we began with the very basics: pronunciation of Chinese phonemes – not an easy feat. To our untrained ears, there is a proliferation of sounds that all sound a LOT alike. Take zh and j, ch and q, sh and x – each pair pronounced almost the same to an American ear, except for small differences in the extent to which your tongue is curled and the level of aspiration. Then, add a vowel or two: ao, ou, uo… Got it?

Even harder than hearing the distinction is recreating the subtlety with our own clumsy western tongues. And, of course, tone matters. If you say “ma” with a first tone, it means “mother”. But, say these same two letters with a third tone and it means “horse” – a source of endless amusement.

Mercifully, Mandarin grammar seems to be extremely simple, at least for the simple sentences we’re building. For example, one of the challenges to learning many new languages is verb conjugation. Take the verb “to be”. In English, we say “I am”, “you are”, and “she is”. It also matters whether you are talking about the past, present, or future: “I was”, “I am”, “I will be”. Mandarin eliminates nearly all of that complexity. The verb for “to be” is “shi” and it stays exactly the same regardless of whether you’re talking about me, you, or a third person. To move through the past, present and future - you just add a simple temporal helper word to the basic verb form.

The upshot of all of this is that in just four days we are already constructing basic sentences – in first, second, and third person as well as in the past, present, and future tense. But, sadly, no one can understand them!

Well, almost no one. We have managed at least a few times to not only ask the price of fruit at the stand near our language school but also understand the response – a big achievement in our books! We’re hoping that with practice we’ll be able to expand this incredibly limited repertoire a bit.

If this leaves you skeptical that three weeks of language study will prepare us to travel in China – trust me, we’re with you. Luckily, our ability to navigate does not rely on our mandarin skills alone. Thank God for technology.

Cell phones are our lifelines here. Pleico is a dictionary app that will also read Mandarin words aloud so you can here how they’re pronounced. WayGo translates menus from Chinese characters to English in real-time. The real gem is the Google Translate app. It can translate entire English sentences into Chinese – both pinyin (for us to read) and Chinese characters (to show a taxi driver or shopkeeper). And it can do the reverse from a photo of written Chinese text. Google Translate even produced an impressive translation of instructions on a box of tylenol. Though imperfect, this all feels more than a bit like science fiction.

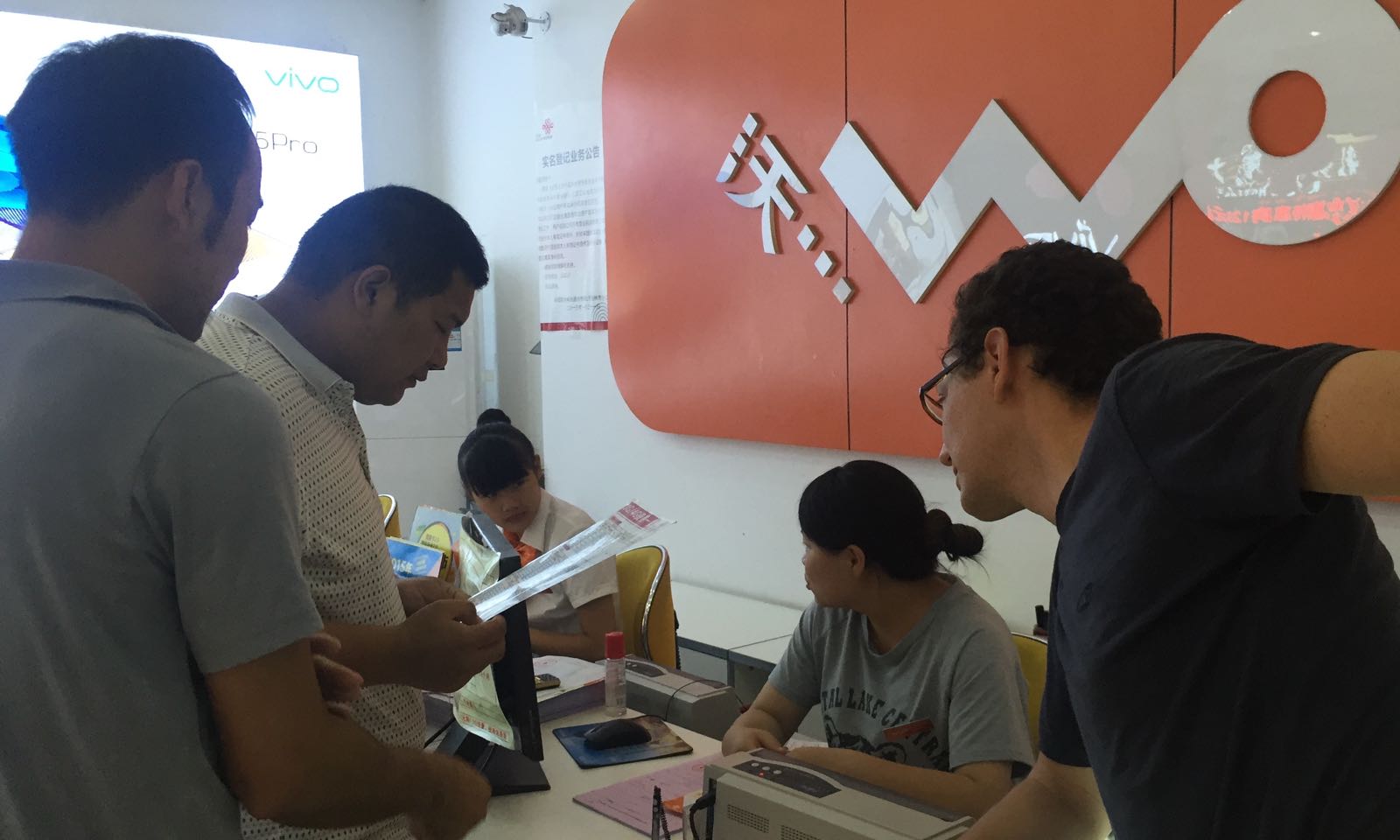

It took four enthusiastic Chinese helpers, three trips to the China Unicom store, two hours of near-total mutual incomprehension, and one healthy dose of persistence to get us our Chinese SIM cards. But oh was it worth it!

It took four enthusiastic Chinese helpers, three trips to the China Unicom store, two hours of near-total mutual incomprehension, and one healthy dose of persistence to get us our Chinese SIM cards. But oh was it worth it!

The value of the Google translate and map apps has proved our greatest motivation for circumventing China’s “Great Firewall.” Any number of commercial VPNs make it quite easy to do so, although the connections are finnicky, particularly when layered onto already-overburdened cellular or WiFi networks. Still, we’ve been surprised by how easy it usually is to get around China’s expansive censorship regime – local businesses sometimes even offer VPN-included Internet.

Outside school, we’ve begun to explore Yangshuo a bit. We spent a glorious morning walking Yangshuo’s public park before finding a shaded spot for some yoga. We were in good company, for the park was filled with locals undertaking various forms of public exercise: tai chi, of course, but also crowds of dancers swinging fans or swords in synchronized patterns (the Chinese apparently call this “square dancing”, though it’s far from the image that term conjures for Americans), as well as an elegantly dressed older couple ballroom dancing to a Chinese hip-hop beat. Meanwhile, a dentist was plying his trade from a mobile cart, a calligrapher wrote out elaborate characters, and groups of old men huddled around tables playing Chinese checkers and card games.

In the evening, we ventured out to West Street (Xi Jie), Yangshuo’s prime evening destination for its abundant Chinese tourists. Busloads upon busloads of people, who spend the daytime in the surrounding countryside, all return each night to this 500-meter stretch of road, which becomes a several-block long pulsing mass of humanity. When the nightly mass migration arrives, this narrow pedestrian avenue in our little rural town makes even Hong Kong’s markets look tame. We stopped at one stall that was selling, for a few dollars, the opportunity to ride a virtual roller coaster on a developer preview of Oculus 3d goggles – we assume either ill-begotten or fake. As advertised, it was both fantastic and nauseating.